Silk Road World Heritage

Both UNESCO and the UN World Tourism Organization have long recognized the need to give greater international attention to the historical and cultural connections and flows of the overland Silk Road, the legacy of which is an array of movable and immovable material culture, including monasteries, post houses, forts, cave temples, Buddhist pagodas, tombs, textiles, documents, leather goods, and ceramics.

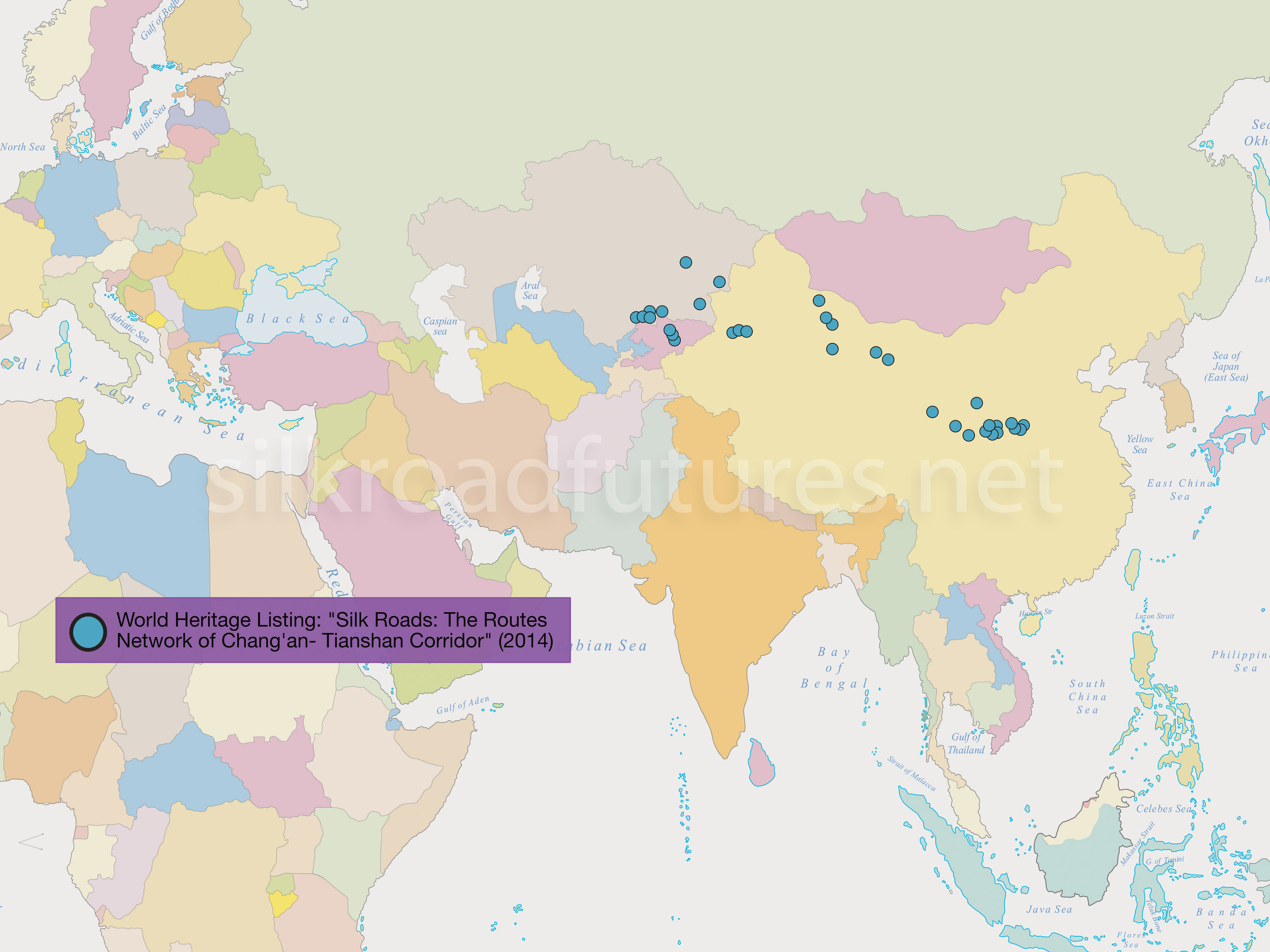

After years of discussion, plans for listing sites of the overland Silk Road as World Heritage formally commenced in 2003. To assist the process, the Intergovernmental Coordinating Committee of the Serial World Heritage Nomination of the Silk Roads was established in 2009, an initiative made possible through the financial support of the Japanese, Norwegian, and South Korean governments. In 2014 the Silk Roads: The Routes Network of Chang’an-Tianshan Corridor was added to the World Heritage List. This included thirty-three separate sites, twenty-two in China, eight in Kazakhstan, and three in Kyrgyzstan.

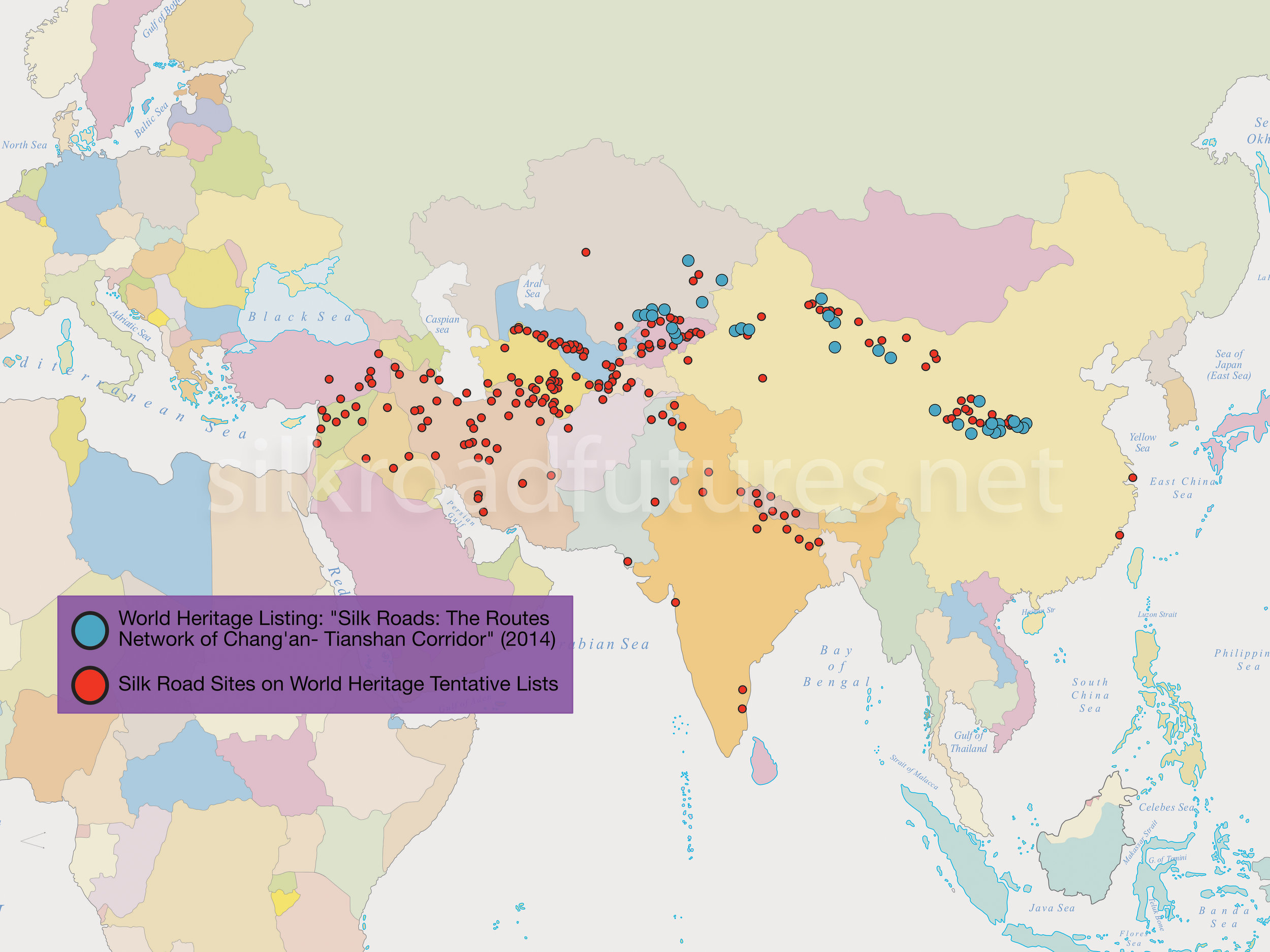

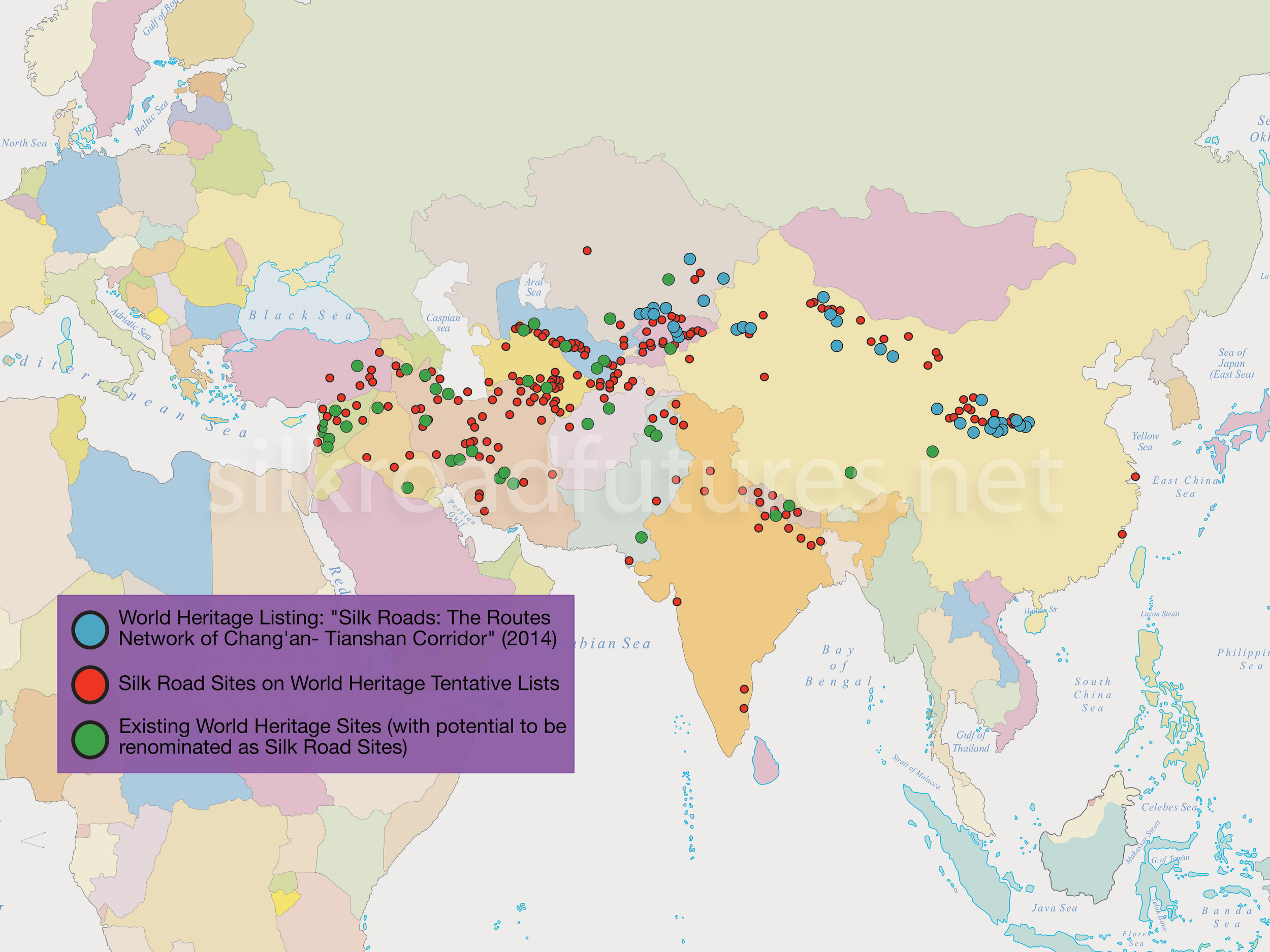

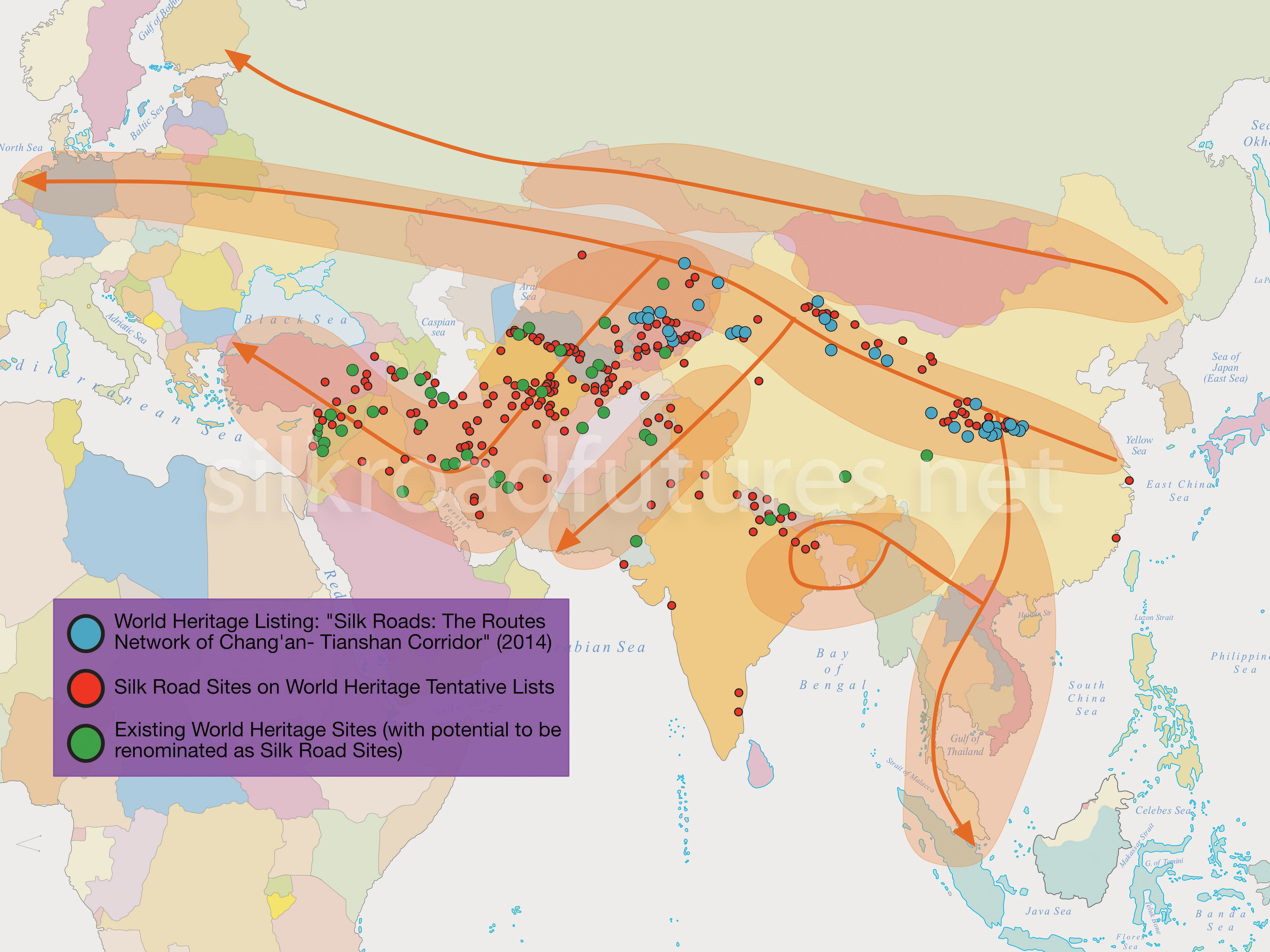

Silk Road world heritage has been guided by a report authored by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS. Published in its final form in 2014, The Silk Roads: An ICOMOS Thematic Study detailed 550 historic settlements, archaeological sites, and architectural structures across the region associated with the Silk Road, grouping them into a series of transnational corridors.

Since 2013 the number of planning meetings for Silk Road world heritage nominations has increased. Kazakhstan has been particularly active in hosting workshops and conferences designed to advance Silk Road heritage cooperation. In late 2015, Nursultan Nazarbayev signaled his government’s long-term commitment to promoting heritage as a mechanism for security, peace, and stability.

Significantly, this wave of activity in creating international collaborations around culture and heritage maps onto the developmental corridors of Belt and Road. Many sites in Central and South Asia are also locations expected to see significant infrastructure development. The story of World Heritage in Asia has been one of land speculation, the elite capture of resources, internal migration, and environmental and cultural pressures created by tourism. Silk Road heritage development will be a complex future of opportunities and challenges. Central Asia in particular is likely to see rapid developmental investment as ever increasing numbers of Chinese tourists venture westwards to visit Silk Road locations. The introduction of high-speed passenger lines between China and Kazakhstan and beyond will likely be a game changer for the region. Silk Road World Heritage also enters a world of disputed borders and highly securitized zones.